‘You’re Not Alone.’ How one PGA of Canada Professional Hopes his Story will Help Others

By: Adam Stanley

Dustin Wilson was upstairs in his home in 2018 when he took what he thought was his final breath. He got “help” out of his mouth and woke up two days later in the hospital.

Luckily his tenant was home, in the basement apartment, and heard him. That person, an EMS, had a Narcan kit and was able to revive Wilson while preforming CPR. He had overdosed on prescription drugs, cocaine that was laced with fentanyl, while mixing alcohol at the same time.

The ambulance came to take Wilson to the hospital and revived him again in the ambulance on the way to the emergency.

Wilson, a PGA of Canada member for 21 years, has been sober now for eight months. He spent 30 days earlier this year at GreenStone, a recovery centre in Muskoka, getting clean. He’s on a day-to-day journey to live a better, cleaner, healthier life.

And there are programs, like the PGA of Canada’s Member Assistance Program and the newly established Benevolent Fund, to help. (The Benevolent fund helps members in need when there is nowehere else to turn).

He's working on his recovery. He wants to help.

Wilson wants his fellow members to know they’re not alone.

“I’m speaking out as someone who is in recovery. Not someone who is recovered from addiction,” says Wilson. “You might have a year or two or 10 years when you’re an addict in recovery, but something triggers you to get back. There are guys who come to meetings every day for 30 years because they need to. They’re one drink away from a drunk, and that means they could die.”

Wilson, who is a teaching professional at Whitewater Golf Club in Thunder Bay, Ont. and in sales with BioSteel in the area, has been on a lengthy journey as an addict – he’ll be the first to admit it. It wasn’t always pretty. Still isn’t. But he’s ready to be open and honest – with himself, firstly – and he wants his fellow PGA of Canada professionals to know that there are opportunities for help.

“I’m present,” says Wilson. “I’ve quit a few times but gone back and forth (with being sober) because I’ve tried to save a relationship, or not get in trouble with the law, or not pi*s my mom off. It took a lot of courage for me to (get completely sober).”

Wilson was a great athlete, plain and simple, growing up in the Northwestern Ontario sports scene. It wasn’t the biggest for golf, but there was hockey. His mom had him when she was just 19. His dad left when he was young. Wilson didn’t come from much. When he started school, his mom re-married. He took all this hard.

He took his first drink when he was in Grade 8.

“All that pain went away,” he says. “Nothing else mattered.”

Through high school, Wilson was that great athlete that made every team. You know the kind. Every school has one. It was easy, he admits, to succeed. He never pushed himself to be great at anything though – because he was an addict.

When he got to Triple-A hockey there was pressure from parents and coaches and his teammates, which added to everything else he was going through on the home front. He drank more on weekends. He was 16. His mom had separated from his step-dad then and was travelling a lot for work. Drugs like cocaine and ecstasy came hard and fast after he got his drivers’ licence.

He started swinging a golf club as a youngster – about four or five, he says – but had given it up for years. Competitive hockey he kept up with, until he couldn’t. In junior hockey, he says, he was bounced around to every team you could think of.

“Because I tried to be the cool guy and drink,” he says, not really caring about anything else.

That whole year was about partying and drinking and trying to forget the personal traumas he was enduring between the unknown of what this hockey career would be – if anything – and what was happening at home.

Golf came back into his life at 18, though, when he saw a package for a golf program at Georgian College. He ended up there and became a PGA of Canada member, becoming one of the country’s youngest professionals at the age of 19. Wilson went from not playing the game at all to playing all the time. He started to enjoy the game again.

He graduated school and got a job at Glen Abbey. He was introduced to the buzzy golf culture in the Greater Toronto Area, and he fell in love with that.

“I just didn’t fail,” he says. “I was a great people person with awesome social skills and the golf industry just fit right into what I was doing.”

But there wasn’t a true joy there. The addiction issues remained. He was playing and practicing but there was a built-in excuse to drink after work. It was part of the scene there. He was using.

“I was on top of the world, but I wasn’t really living in reality at that point,” he says. “I came from nothing and was spending way more money on drugs and alcohol. I met my (now) ex-partner and we had a kid right away. That changed everything.”

Things began to turn around. When he had a laser-like focus on his job, when he was training for a tournament, or when things at home were manageable, he was alright. But as he got super serious with golf, he was basically replacing one addiction with another.

Wilson returned to Thunder Bay after he became a father for the second time and used that opportunity to come back to reality with his health. He was a head teaching professional at Whitewater Golf Club for a number of years. Teaching was his escape. It gave him something to be proud of, and something to spark happiness by passing along knowledge of a game he was in love with again. One of his students, Dustin Barr, changed his life.

Barr and Wilson were really close. Wilson says he went “all in” on helping his pupil. But Barr was unfortunately diagnosed with a rare cancer and had tumours on his pelvis and pancreas. Through Barr’s chemotherapy treatments, Wilson’s demons returned. He separated from his partner then. His drinking and using became very heavy.

“That look a lot out of me and my life,” he says. “And I started to lose things in my life at that point.”

He detached from golf and became a car salesman. But after going in for back surgery, he got addicted to prescription drugs. It was another challenge to get over, and he would never admit to himself he was in trouble. People around him tried, of course, but he was still trying to live up to a public image he had built up for himself as this ultra-cool, big-city golf guy.

“It wasn’t really reality at all,” says Wilson. “I still had this love for the game and understanding and I wanted to be a teacher to help kids. That was my dream. I never let that go.”

Barr ended up having a big Make-A-Wish dream come true that took him to play many of the game’s iconic layouts in Scotland like The Old Course, Turnberry, and Muirfield. After that trip, Barr had a 24-hour surgery in Toronto, and within 18 months he was back learning to walk and playing golf again. Barr earned a scholarship to a school in Georgia, but after his sophomore year, he got sick again. Barr passed away in March of 2020.

A mix of things happened for Wilson after Barr’s death.

Wilson started a charity with Barr’s family, who he had become quite close with, to raise funds for organizations in Thunder Bay and the surrounding area that had supported Barr through his seven-year battle with cancer. This is the third year, and the organization is trending towards raising more than $180,000 by the end of this summer.

But the COVID-19 pandemic, Wilson says, was terrible for him.

He got laid off from his car sales job and began drinking even more. He was using. He was taking prescription drugs. He had a new partner that he loved, but he was almost back to square one. Alcohol would be part of his daily routine, like someone else’s’ morning coffee.

He would drive his kids to school and would “slam” a beer. He’d drop them off and drink on the way home. He’d pass out for a couple of hours.

“I was going to lose everything,” says Wilson. “I needed help.”

He got it at the treatment centre in Muskoka, a place he checked in to in January of 2022.

“Over half my life I’ve lived on alcohol and drugs, and I’ve done some crazy successful stuff that most people probably couldn’t do. But I was a functioning alcoholic and addict. My talents were used in a manipulative way,” he says. “I was doing everything for everyone else and I was using drugs and alcohol to cope with my own problems, which I never dealt with.”

When Wilson came out of the 30-day treatment effort the concern that remained was what was to come next. He was returning to Thunder Bay, the lion’s den for his issues. Was he going to be OK?

For more than two decades he was part of the PGA of Canada and saw the Members Assistance Program that was there, but nobody really talked about. He leaned into it. He took it one day at time. And support is there.

“It gives our members somewhere to turn,” says Kevin Thistle, the CEO of the PGA of Canada.

Wilson is a real person from a small town that never had anything growing up, he says. He accomplished a lot, and he lost everything, and he fought back. This September he’s going to tee it up at the PGA Assistants’ Championship of Canada presented by Callaway Golf. He hasn’t played a national open for more than 10 years. Golf is part of his recovery plan – because he’s never done it sober. It’s overwhelming and it’s hard, but it’s also rewarding, he says.

Wilson is mending fences. He wants his life to be filled with joy, and he wants to help – whether it’s a youngster trying to make it to the next stage in their golfing life or a fellow PGA of Canada professional who has nowhere else to turn.

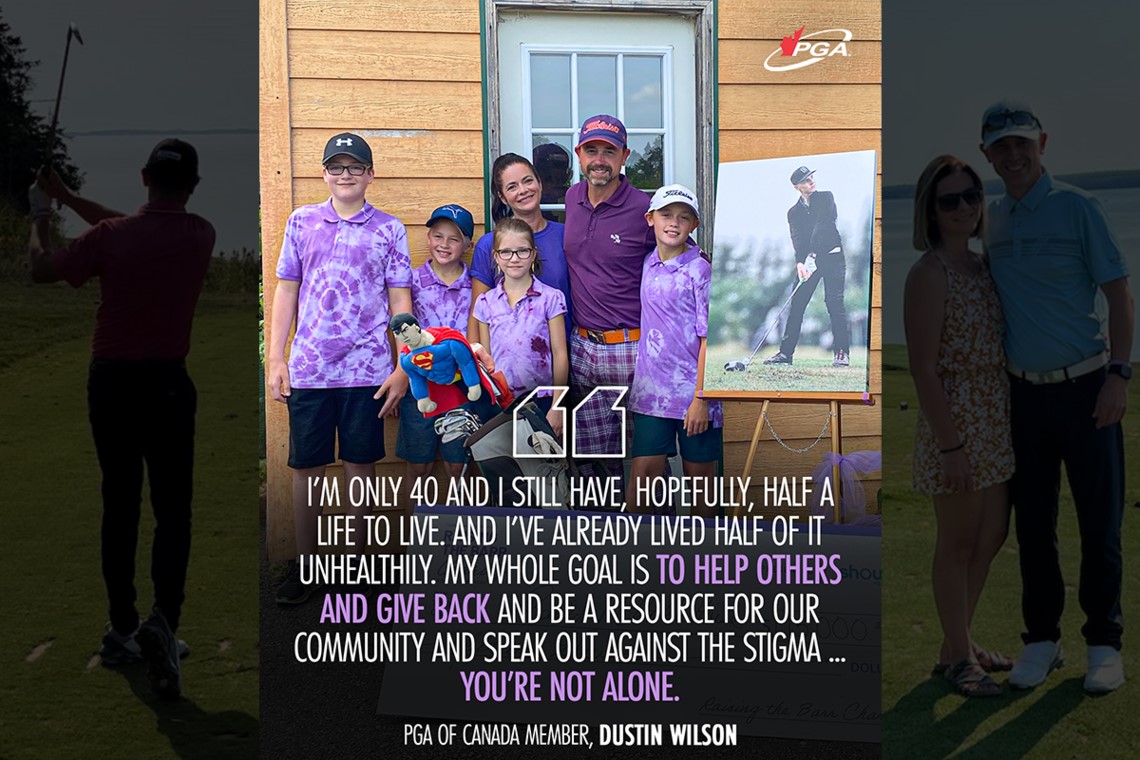

“I’m only 40 and I still have, hopefully, half a life to live. And I’ve already lived half of it unhealthily. My whole goal is to help others and give back and be a resource for our community and speak out against the stigma,” he says. “You’re not alone.”

-30-

If you’re struggling with mental health, substance abuse, or in need of a place to turn, learn more about the PGA of Canada’s 24/7 Members Assistance Program here, and the new PGA of Canada Foundation Benevolent Fund here. All donations to the Benevolent Fund go to members in dire need. Dustin Wilson can be reached at dwilsonnwogolf@gmail.com.